For a lot of people, the name of John Calvin is synonymous with Orthodoxy. He’s seen as a brilliant systematic theologian, biblical scholar, and the scourge of heretics. But was he really the upholder of Orthodoxy as so often thought. My suggestion is that he was not. I believe that the underlying presupposition of Calvin as a defender of Orthodoxy is the false dichotomy between Orthodoxy (Right Belief/Teaching) and Orthopraxy (Right Practice/Behavior).

Two Modern Opposing Extremes

In today’s culture, and even 500 years ago as we will see, there is a belief that Christianity is either all about Orthodoxy or all about Orthopraxy. In more fundamentalists circles it tends to be all about right belief. Whereas with Christians from the Mainline Protestant churches (many who are former fundamentalists who are burnt out on the notion of Orthodoxy) Christianity is really about our behavior. Heresy then has been relegated to false belief and has become something that many from mainline denominations are extremely uncomfortable with. This discomfort is I think due to the fact that the term heresy has been used to hurt people. But just because some have used the concept of heresy to hurt others doesn’t mean there’s no such thing as heresy. It would be wise of the church to avoid these two extremes.

An Unpleasent Day in Geneva

I suppose the best place to start my response to your thoughts would be with a story. Long ago in a beautifully nestled city in the French alps called Geneva lived one of the Protestant Reformers named John Calvin, a french man himself. He was a staunch defender of what would come to be known as Protestant theology. He was also a brilliant man. His “Institutes of the Christian Religion,” a big chunk of systematic protestnat theology, probably the first of its kind was started by him at the age of 19, and finished by the time he was 24.

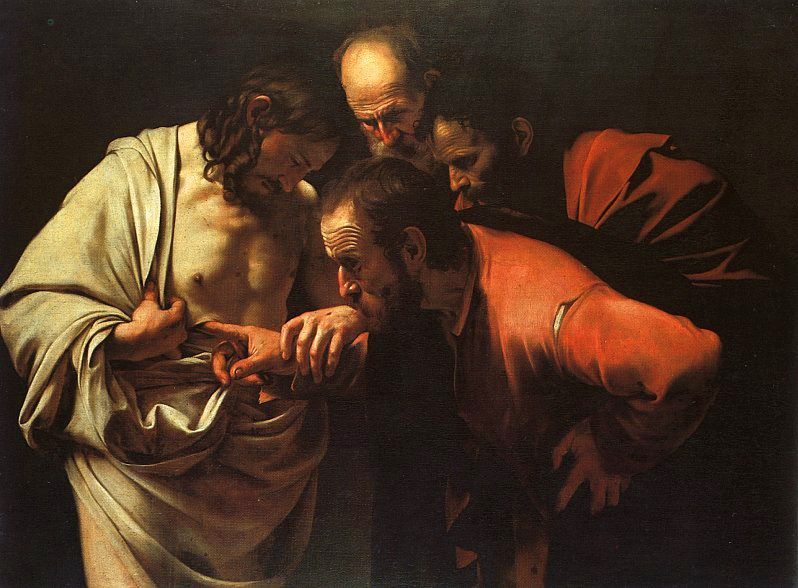

He came to be one of the key leaders of the city, a city ran as a theocracy. There also was a man named Michael Servetus who was a heretic, because, in fact, he denied the Trinity. Hunted by both Protestants and Catholics alike he was a wanted man was he. Micahel had recently escaped prison in France where he was being tried for heresy by the Catholic Church. Well, Mikey eventually wandered into their little slice of heaven here on earth [Geneva], and of course, was recognized and caught. The city officates wanted to have him burned at the stake but Calvin (not Klein) was merciful and suggested they merely cut his head off. However, the rest were not swayed and Servetus was indeed burned at the stake. So just as Saul had stood aside giving his approval, so did John stand aside giving his approval to the execution of Michael (even if not to the manner of execution). It was a day of victory, for the rotten decay of heresy was cleansed from their city. Or so the story goes. For that day heresy now raged on disguised hiding in plain sight. There among those simple city folk lay still a denier of the Trinity, nay I should say, lay many deniers.

Heresy Incognito

For, there are multiple ways to deny the trinity. One way as we have seen is to do so intellectually as Michael had. Another more devious way, one masked in “piety” is to relinquish the peace of love and attack the image of God. So you see that the God who is Trinity is so because He is Love. And He is Love because he is Trinity. To reject love, which does no harm, is none other than a denial of the Trinity. The call to love God and neighbor is tied to the doctrine and reality that God is Love because God is Trinity, an eternal community of mutual self-giving love.

The Orthodoxy of Love

Love And Orthodoxy go hand in hand. In other words Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy are not separate, to deny either one is heretical. You cannot separate them without throwing them both out. By killing his fellow image bearer and thus relinquishing Love, Calvin in practice denied that very Love, thus denying the Trinity. Ironically by trying to use Hate, the absence of Love, to purge heresy from this earth he in fact accepted that very heresy. Ultimately our behavior is intrinsically tied to our orthodoxy, and how we interact with those who have departed from orthodox doctrine will determine our own orthodoxy.