It was cold and wet. Quiet permeated as the sun gently rose over the tree-lined ridge. The trails were muddy at the Abbey. The flow of air into my out-of-shape lungs was shallow and swift as I climbed the hill that, at the moment, felt like a mountain. I took the first right turn off the main path onto a grassy, more level way. It provided a chance to catch my breath. The sun was shining warm on my face when I stopped at a large tree stump just before the shade of the woods. Though everything was wet from the night rains, I sat.

I dug into my jacket pocket and pulled out a bag of rocks. I’ve walked these Abbey trails before, and there are places along the paths where people leave trinkets symbolizing burdens and hopes. Once, I walked with no trinkets to leave, but today, I’m ready. I have five rocks in my bag. I pull out one of my favorites, a rock from the Oregon coast, speckled with white dots in a tan-ish surround.

I held the rock and consider belonging. The birds belonged there. The trees and paths all belonged there. I belonged there, if even only on occasion when I’m gifted with time to retreat from the usual. But the rock, it didn’t belong there. As I looked around, there were no others like it. The rocks on the paths were black and sharp; gravel laid for traction. Ocean-worn rocks were nowhere to be found in the meadow.

Since walking away from my evangelical faith community two years ago, I’m a bit like the speckled rock. For more than twenty years, I was firmly situated in various evangelical communities, the first being the United Methodist Church, the last, a conservative non-denominational. I found comfort in the close community and Christ-centered teaching. I loved attending group bible studies and served tirelessly within the community, discipling and caring for the needs of others. I enjoyed the fruits of the evangelical foundations laid long ago, that was until I attend seminary. While working on my Master of Divinity, I was introduced to biblical exegesis and criticism, church history, and a wide array of spiritually formative practices utilized by faithful Christians throughout millennia. This new-to-me information, combined with personal suffering, initiated a season where the theological and formational religious structures I once existed in crumbled, leaving me wandering in a spiritual wilderness, no longer quite belonging anywhere.

I wonder if that’s how many Christians felt in the 1700s, when industry and plagues swept the landscape of the nations, causing uncertainty and strife between the haves and have nots, the healthy and the ill? In a time of religious, economic, philosophical, and social turmoil, a remedy was sought. As with many Christian movements, evangelicalism emerged in response to and was formed in a culture where Church religiosity and Enlightenment reason reigned supreme. Conversionism, biblicalism, activism, and crucicentrism became the foundational components of this newly emerging sect of Protestants.[1]

Enticed by language communicating assurance, many, by putting their faith in Jesus, were “converted” from their sinful ways, to take the moral high-road paved with hard-work, financial resources, and care of their neighbor.[2] Furthermore, this “faith of assurance” helped those feeling lost and uncertain of their eternal fate have a sense of divine security.[3] It is out of gratitude for this assurance that activism flowed. The work to bring about converts was laborious and never ending. “Consistency, seriousness, and fervid energy (were required for) industry, patience, and self-denial,”[4] the core characteristics required of those working to save the lost. Regarding biblicalism, evangelicals held scripture in the highest regard. Literalism and inerrancy soon became key components of the evangelical faith, where purposefully selected words in scripture brought about a certainty that God was, is, and will forever be with them in the earthly and heavenly realms.[5] Crucicentrism, or the doctrine of the cross, was the final cornerstone of evangelical faith. For them, the atonement was central to understanding why Jesus was even born, for salvation only comes through the death of Christ.[6]

It’s been almost 300 years since evangelicalism emerged on the Christian landscape. Overtime, different camps formed, and division emerged, each pointing to scripture for their reasoning. Even still, evangelicalism has stood the test of time, profoundly shaping and being shaped by political, socio-economic, philosophical, and cultural moods. Though large shifts regarding doctrine, piety, opinion, practice, eschatology, and spirituality occurred, evangelicalism has remained grounded in its four main tenants.[7] While those tenants brought certainty and assurance to many, they also isolated and condemned others. The roots of isolation and condemnation run deep, and the effects of the evangelical beliefs are evident today, especially within more fundamental and conservative groups, who professing to love Jesus and desire to share the gospel have a keen distaste for people different than themselves. [8] ,[9]

We still live in uncertain times, but it is evident the pendulum of evangelicalism has swung too far right, and the hope it once provided is minimal. Its reign is diminishing, for missing from the heart of evangelicalism is a sense of wonder and awe about this Holy God they profess to believe in. Missing is the thoughtful perplexities that come from a contemplative experience of the mysterious Divine. Missing is the reality that God is both knowable and unknowable. Missing is the generosity of spirit and radical hospitality for all people, that accompanies the grace of God through Jesus Christ. Instead, exclusion, prejudice, judgment, and isolation prevail in the name of Christ, and thus serves no one well. Especially Jesus.

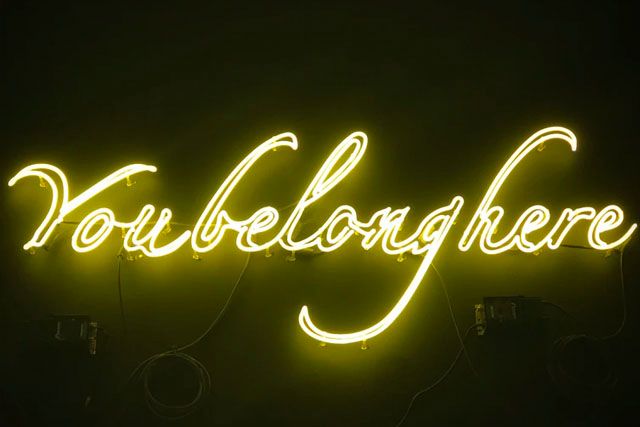

Its premises, while once purposeful, no longer provide comfort in a time when countless are crying out to be seen, heard, and belong. The time has come to allow the wonder and mystery of God, through Christ’s Spirit, to flow freely into the margins and broken places of the world. The time has come for evangelicals to live like Jesus, not just be assured they have been saved by Jesus and convince others to be saved, as well.

As my walk along the Abbey trails neared conclusion, I went back to the large tree stump and left that speckled coastal rock on top. It was my attempt to reconcile paradoxical realities of sea and land, of belonging and not belonging.

Isn’t that like the grace of God though, to unify, through Christ, the paradoxes of this world, to mend brokenness, and to give hope and life where there is none?

Bringing such unity and healing requires something new, speckled with some of the tried-and-true old. Brian D. McLaren, in his essay “Three Christianities,” notes, “(A) new kind of Christianity can only emerge as a trans-denominational movement of contemplative spiritual activism.”[10] McLaren and myself, like countless others before and beside us, are trying to figure out this Way of Jesus, and then faithfully follow. By examining historical and traditional successes and failures, we are privileged to join the “great cloud of witnesses” to help pave the way through the now into the next, so the glory of God and the love of Christ reveals to others that they, too, belong.

Photo by Amrit Sangar on Unsplash

[1] D.W. Bebbington. Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (New York, NY: Routledge, 2005) 3.

[2]Ibid., 5.

[3]Ibid., 7.

[4] Ibid., 11.

[5] Ibid., 13.

[6] Ibid., 14.

[7] Ibid., 271-276.

[8] Ibid., 275. Bebbington defines fundamentalism in theological terms as “a deductive approach to biblical inspiration, the belief that since the Bible is the word of God and God cannot err, the bible is inerrant.” He goes further to include a social definition that “describes a group so fanatically committed to its religion that it lashes out against opponents in mindless denunciation.”

[9] Ibid., Chapter 4, The Growth of the Word: Evangelicals and Society in the Nineteenth Century.

[10] Brian D. McLaren. 2019. “Three Christianities.” Oneing: An Alternative Orthodoxy 7, no. 2: 71.